Don’t hesitate — take advantage now of our special Black Friday 80% Lifetime Deal. This offer is only good until December 25, so what are you waiting for? $6 for an annual subscription! Where else can you find bargains like this?

Many angry atheists will tell you (and tell you, and tell you) that they rely on facts and evidence rather than regurgitated Bronze Age myths sky-daddy myths. But while it’s easy enough to make fun of the fedora brigade, let’s look to some kinder, gentler, and smarter unbelievers. A 2021 Humanists UK handout states their position:

Many atheists believe that the responsibility should rest on the believer to provide good evidence that something exists, not on the non-believer to prove that it doesn’t. This is because it is impossible to prove that something does not exist.

That’s a reasonable request. But what facts and evidence would they accept as proof of Sky-Daddy’s existence?

Atheists quite sensibly reject religious texts as self-recursive evidence.

“We know God exists because [Holy Book] says so.”

”How do we know [Holy Book] is correct?”

”Because it was written by God.”

While you may find inspiration from those texts, and may decide for yourself they are divinely inspired, you won’t get the kind of proof that stands up in a lab or a courtroom. Neither would any theologians worth their salt tell you otherwise.

For something more concrete, let’s consider miracles. Humanists UK tell us that atheists “don’t believe in ‘miracles’ – they believe either these events have a natural explanation or they simply didn’t happen.” Turning to the believers camp, let’s take a look at a miracle attributed to St. Josemaría Escrivá — the cure of Dr. Manuel Nevado from cancerous chronic radiodermatitis, an incurable disease, which took place in November 1992.

A specialist in orthopedic surgery, [Dr. Nevado] operated on fractures and other injuries for nearly 15 years with frequent exposure of his hands to X-rays. The first symptoms of radiodermatitis began to appear in 1962, and the disease continued to worsen. By 1984, he had to limit his activities to minor operations because his hands were gravely affected. He stopped operating completely in the summer of 1992, but did not undergo any treatment.

According to a 2016 PubMed paper on cancerous chronic radiation dermatitis:

Clinical manifestation includes changes in skin appearance, wounds, ulcerations, necrosis, fibrosis, and secondary cancers. The most severe complication of irradiation is extensive radiation-induced fibrosis (RIF)… Chronic radiation dermatitis is usually an irreversible and progressive condition, which may heavily deteriorate patients’ quality of life.

That November, Nevado was gifted with a prayer card of the recently beatified Escrivá, the founder of Opus Dei. Nevado petitioned Escrivá for relief from his condition. A fortnight later the lesions on his hands had disappeared. By January of 1993 Nevado returned to his profession.

Examinations of the Medical Committee of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in 1993, 1994, and 1997 found that Nevado’s healing was “very rapid, complete, lasting, and scientifically inexplicable.” With this evidence, the Blessed Josemariá was promoted by canonization to St. Josemariá.

The Congregation for the Causes of Saints receives thousands of reports of miracles each year. Only a handful are approved after extensive research by clerics and lay experts. Doctors working on behalf of the Congregation described Nevado’s remission as “scientifically inexplicable.”

You could object that these doctors were biased or claim that Dr. Nevado’s cure never happened. But unless you are a medical doctor with access to Nevado’s records, you’re simply dismissing inconvenient events as fake news without any evidence or credentials to back your assertions. Which is hardly the sort of behavior we expect from people who prioritize evidence, facts and logic.

A more educated atheist might note that miracles are not repeatable. You can’t create an experiment that determines what conditions make miracles more or less likely. And even a Christian believer has to acknowledge reports of miracles in Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and other religious traditions. (Heck, this Catholic has seen inexplicable things happen at Vodou ceremonies).

While miraculous events suggest our understanding of the universe is incomplete, they may not qualify as evidence of God’s existence — or as proof that your religion is superior to anybody else’s. So if miracles won’t convince an atheist, would a personal visit from God do the trick? Alas, no.

[O]ur modern understanding of human psychology and neuroscience is making it easier to understand where such experiences come from. Scientists have even managed to trigger ‘religious experiences’ in experiments by stimulating particular parts of the brain.

Many people have reported mystical experiences of God or God’s emissaries. But brain dysfunction and hallucinogenic substances can induce very similar visions. Would you be willing to take God at face value if he showed up at your home for a chat? If you did, how would you convince others that He exists? If you read up on the lives of the Saints, you’ll find that their visions met lots of skepticism even from believers. And if you check your Bible (or your Q’uran), you’ll see warnings to shun a man who convinces the world he is God. Muslims call him the Dajjal: Christians call him the Antichrist.

We must cede at least one point to the atheists: it’s impossible to prove the existence of God. But while they are incapable of finding positive proof, they have some rather compelling evidence against a divine Creator.

We’ve known since time immemorial that our world is full of evils. Many Eastern religions seek an escape from the endless Wheel of Death and Rebirth. The Gnostics saw our world as a prison built by a cruel and incompetent Demiurge who trapped spirit in matter and light in darkness. Jews, and later Christians, blamed our plight on a sly Serpent and a tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

We can’t fault atheists for thinking that no all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-loving God could create so much suffering and injustice. Every day a multitude of innocents are starved, raped, and tortured while a loving God looks on and fails to intervene. Every day people die in disasters they might have avoided had God warned them. Every day good people fail and bad people succeed.

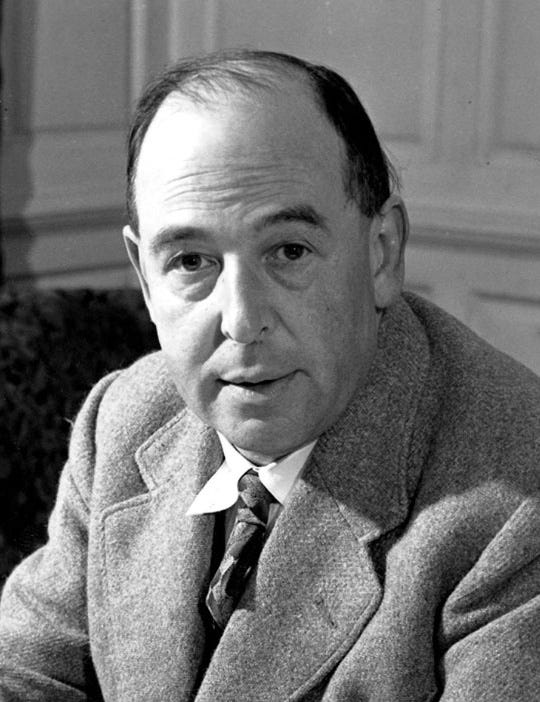

Certainly the problem of pain tries our faith in God’s benevolence. After C.S. Lewis lost his wife to cancer, he wondered if perhaps God was a Cosmic Sadist and Eternal Vivisector. But ultimately Narnia’s architect found his way out of that darkness.

The terrible thing is that a perfectly good God is in this matter hardly less formidable than a Cosmic Sadist. The more we believe that God hurts only to heal, the less we can believe that there is any use in begging for tenderness.

A cruel man might be bribed—might grow tired of his vile sport—might have a temporary fit of mercy, as alcoholics have fits of sobriety. But suppose that what you are up against is a surgeon whose intentions are wholly good. The kinder and more conscientious he is, the more inexorably he will go on cutting. If he yielded to your entreaties, if he stopped before the operation was complete, all the pain up to that point would have been useless.

But is it credible that such extremities of torture should be necessary for us? Well, take your choice. The tortures occur. If they are unnecessary, then there is no God or a bad one. If there is a good God, then these tortures are necessary. For no even moderately good Being could possibly inflict or permit them if they weren’t. (A Grief Observed, 42)

Ultimately suffering— like science, mathematics, philosophy, and everything else — can neither prove nor disprove the existence of God. Those who insist on evidence and those who claim to have evidence are equally misguided. For those who believe in God, miracles are signs that strengthen their belief. For those who do not believe, those same miracles are signs of human gullibility. Abbé LeMaître looked at the stars and saw God’s creation at work. Atheists look at the sky and see proof that Genesis is just a silly story.

From a materialist perspective pain is easily enough explained. Negative signals stop us from doing things that might harm our bodies. Even a flatworm can learn to avoid a path after experiencing the discomfort of an electrical shock. Our ability to distinguish between good and evil is more challenging. As Lewis noted in his 1940 book The Problem of Pain:

All the human beings that history has heard of acknowledge some kind of morality; that is, they feel towards certain proposed actions the experiences expressed by the words “I ought” or “I ought not”. These experiences … cannot be logically deduced from the environment and physical experiences of the man who undergoes them. You can shuffle “I want” and “I am forced” and “I shall be well advised” and “I dare not” as long as you please without getting out of them the slightest hint of “ought” and “ought not”.

And, once again, attempts to resolve the moral experience into something else always presuppose the very thing they are trying to explain — as when a famous psycho-analyst deduces it from prehistoric parricide. If the parricide produced a sense of guilt, that was because men felt that they ought not to have committed it: if they did not so feel, it could produce no sense of guilt.

C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain, 6

You could object that moral codes differ greatly between different cultures, though you’d have to acknowledge that murder, incest, theft, and many other actions receive near-universal condemnation. But here Lewis makes another observation: wherever you go, you’re sure to find that the locals preach one thing but practice another.

All men alike stand condemned, not by alien codes of ethics, but by their own, and all men therefore are conscious of guilt. The second element in religion is the consciousness not merely of a moral law, but of a moral law at once approved and disobeyed. This consciousness is neither a logical, nor an illogical, inference from the facts of experience; if we did not bring it to our experience we could not find it there. It is either inexplicable illusion, or else revelation.

Freud and the Frankfurt School saw sexual repression at the root of all our sufferings. They might have done better to ask themselves why we have eternally bound ourselves under laws we cannot follow. On the other hand, given the consequences of the Sexual Revolution, we might be thankful they lacked the imagination to carry their ideas to their logical conclusion.

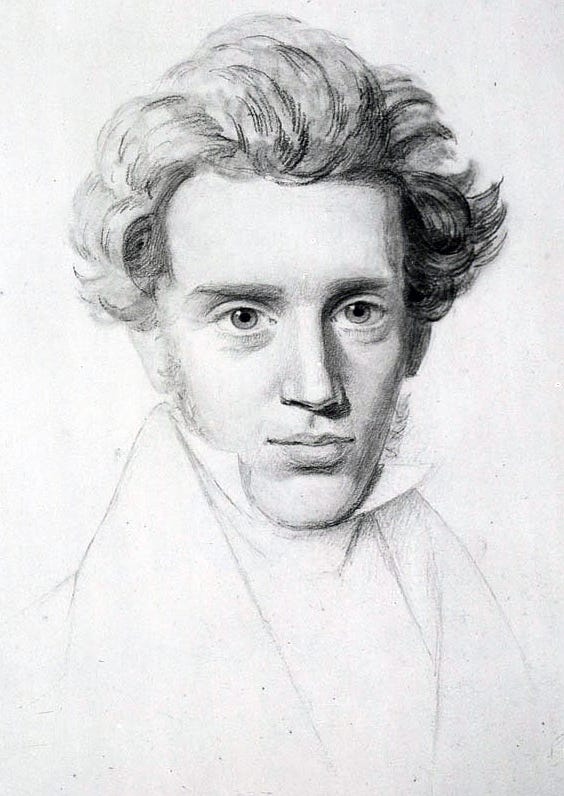

The last thing that human thinking can will to do is will to go beyond itself in the paradoxical. And Christianity is precisely the paradoxical. Mendelssohn says: ‘To doubt whether there may not be something that not only surpasses all concepts but also lies completely beyond the concept, that I call a leap beyond oneself.’

Søren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Transcript, 89.

Kierkegaard wrote his Concluding Unscientific Transcript under the pen name Johannes Climacus. His pseudonym was inspired by the Greek monk John Climacus (c. 570-649), author of Klimax tou Paradeisou (translated into Latin as Scala Paradisi), or Ladder of Paradise. While Kierkegaard’s Climacus is not a believer, he attempts in Concluding Unscientific Transcript and its predecessor Philosophical Fragments to learn what it means to be a Christian.

Kierkegaard/Climacus dismisses objective thinking, research and study as a way of understanding Christianity. As he puts it:

[W]hen faith begins to feel ashamed of itself, when like a sweetheart not content with love but slyly ashamed of the beloved, and so needs it to be recognized that there is something exceptional about him, that is to say, when faith begins to lose passion, that is to say, when faith begins to cease being faith, it is then that the proof becomes a necessity, in order to enjoy general esteem on the side of unbelief. (Transcript, 26)

But he also recognizes the other great limitation of objective thought: that at worst it can lead us astray while at best it can only bring us to an ever-closer approximation. The objective is ultimately part of what Kierkegaard called the Aesthetic sphere. It is focused on the here, the now, and the self. Using objective thought, René Descartes could only say with certainty, “I think, therefore I am.” Faced with the possibility that he was trapped in an illusion created by an Evil Demon, Descartes could only respond with the faith-statement that the perfect God is no deceiver.

Ethics had received careful scrutiny from Kant and Hegel, who both sought a universal ethical code based on reason and social order. For Kierkegaard the Ethical sphere was a higher stage of existence. Those living in the ethical sphere came to recognize their duties to their neighbors and to God. Only when we move from the Aesthetic “what can I do” to the Ethical “what should I do” can we begin to call ourselves Christians in any meaningful way.

But Kierkegaard also warned that many go through the motions of ethics without actually engaging with the highest Religious sphere. As he satirically describes it:

‘Aren’t you a Dane, and doesn’t the geography book tell us that the prevailing religion in Denmark is Lutheran Christianity? You aren’t a Jew, or a Mohammedan; so what can you be? After all, a thousand years have gone since paganism was replaced, so I know you are no pagan. Don’t you attend to your duties at the office as a good civil servant should; aren’t you a good subject of a Christian nation, a Lutheran Christian state? Then you must be a Christian.’

You see? We have become so objective that even a civil servant’s wife argues to the single individual from the whole, from the state, from the idea of society, from geographical science. So much is it a matter of course that the individual is a Christian, a believer, etc., that it is foppery to make a fuss about it, or even a freak of fancy.(Transcript, 44-45)

This ethical Christianity has its merits. Its adherents generally avoid the excesses of the dandy and the aesthete and fulfill all their social responsibilities. They may even engage in the self-analysis and reflection that begins our movement toward the religious sphere. But they never make the leap of faith that would bring them in touch with the God they claim to worship.

We see this leap in Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard’s analysis of the binding of Isaac. From a rational standpoint, Abraham’s journey to Mount Moriah is madness. From an ethical interpretation it is evil. Yet Abraham persists. God has promised Abraham that he will be the sire of nations: in their old age He gifted Abraham and Sarah with a child. As he journeys, Abraham trusts in that promise. And because he trusts that promise even as he raises the knife to slay his son, God fulfills it.

For Kierkegaard Abraham’s trust and resignation to God’s will make him a knight of faith. But most knights of faith face far less cinematic trials. Since the leap is an internal affair, there are no external signs that would distinguish a knight of faith from anyone else passing by on the street. The knight of faith lives in a world that he has renounced. He lives in the finite but exists in and for the infinite.

From the Ethical sphere lovers can gain in marriage joys that the Aesthete will never experience in a million seductions. Those who reach the Religious sphere gain a still deeper understanding of both the preceding stages on life’s way. From that perspective they may accomplish great things, or they may be dismissed as madmen by those who cannot and will not follow them in the leap, those who remain in ethical good graces but in Sartrean bad faith.

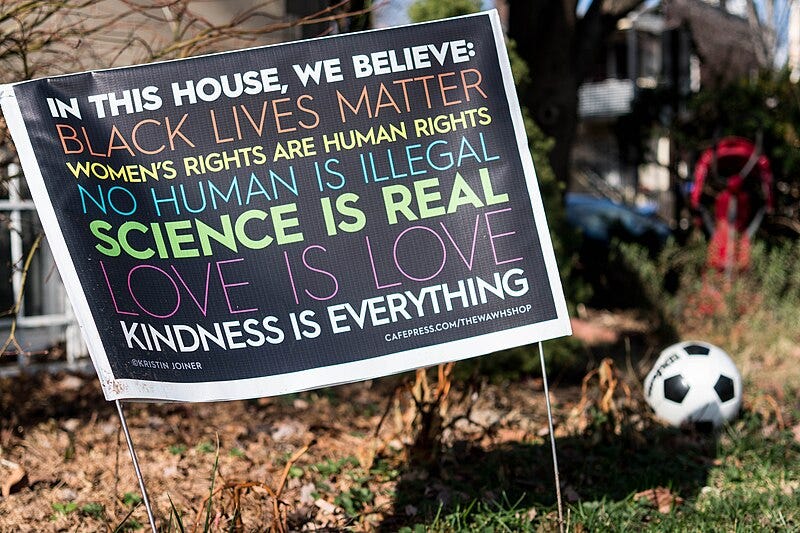

The realm of politics exists, or should exist, in the Ethical sphere. But in modern society most political sloganeering is Aesthetic. Individuals choose their politics not because they want to change the world but because they want social status. They support currently fashionable causes not to do good but to look good.

When wealthy White Americans decided in the wake of George Floyd’s May 2020 death that evil White police officers were killing innocent Black people en masse, they decided the best way to solve these issues was to “defund the police” and to burn several cities in protest.

In 2020 249 Black people and 411 Whites were killed by police officers. In 2021, after police officers in several states were convicted of murder after shooting suspects, those numbers dropped to 165 and 314. But while police-related deaths dropped, other numbers spiked.

In 2017, the year that “In This House We Believe…” signs first began appearing in suburban homes across the country, there were 18,180 murders and non-negligent manslaughters. In 2020 that number rose to 22,510. That number has dropped since then, but only because many law enforcement agencies no longer submit crime data to the FBI.

According to a February 2024 PLOS ONE report, the most recent race-specific age-adjusted homicide rates are:

33.6 per 100,000 for African American persons

12.9 for American Indian and Alaska Native persons

6.9 for Hispanic persons

3.3 for White persons, and

1.7 for Asian and Pacific Islander persons.

Many will cheerfully note that Black Americans are more likely to commit violent crimes, and they’re not wrong. But intra-racial crime is more common than interracial violence, and so Blacks are also far more likely to be the victims of violent crimes. But there are no villains to pillory, and no quick and easy solutions to be offered.

And so it seems that these lost Black Lives (13,406 in 2022) don’t Matter enough to deal with uncomfortable questions. Other than platitudes about owning privilege and standing as an ally against racism, prosperous White folks have shown very little interest in talking about problems within the Black community that are far more pressing than trigger-happy police officers.

When it comes to facts, Aesthetic politics chooses based on popularity rather than scientific rigor. They “Trust the Science” because their social circle trusts the science. They shun “fake news” and rely only on the sources their friends deem reliable. And to make matters worse, the currently fashionable ideology believes that facts are whatever you feel they should be.

An Ethical government ruled by politicians who had motives beyond gaining power and lining their pockets would certainly be a step up from the current state of affairs. Many have grown weary of secularism and have decided that politics should be influenced by religion. But all the problems Kierkegaard noted in 19th-Century Denmark remain alive today. Just 27 years after Kierkegaard’s 1855 death, Nietzsche proclaimed in The Gay Science “God is dead.”

Those who learn from the past have a tremendous advantage over those who wish to tear it down. But any attempt to turn back history is doomed to failure. Even if we could RETVRN to the days of the Founding Fathers or the Crusader Kingdom, we would simply put into place the laws and customs that led us to our current state. If we worship ashes, we’ll never preserve the fire. Let the dead bury their dead. And let those who dare make the leap.

Let us not mock God with metaphor,

Analogy, sidestepping, transcendence,

Making of the event a parable, a sign painted in the faded

Credulity of earlier ages:

Let us walk through the door.

The hedonist/aesthete/addict all suffer without often admitting to it:

The need for another pleasure, because it is fleeting.

You rarely find people of faith suffering such continual desire for a new stimulation.