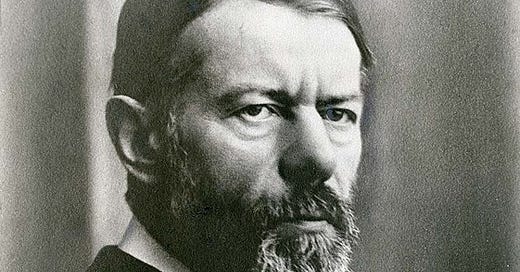

Americans have historically looked down our noses at sluggards and layabouts who refuse to contribute their fair share. We have also held fast to a belief that anyone with enough drive and determination can succeed with enough effort. Today we still distinguish between the “deserving poor” and the parasites who just want to leech off the government. Much of this can be laid at the feet of what sociologist Max Weber called in 1905 the Protestant work ethic.

In 1905 Max Weber released Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus. Translated into English in 1930 as The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, it is considered one of the most influential sociological texts ever written.

For Weber, one of the driving factors of Capitalism’s rise was Calvinism and its emphasis on predestination. Calvin, who steadfastly renounced Justification by Works, suggested that the Elect would behave in a manner that gave glory to God in accordance with their station. This meant, among other things, that they would work industriously at their trade and refrain from wasting money on luxuries.

Unsurprisingly, those who work hard and live modestly tend to have more savings and greater business success than those who do not. For Calvin and other Protestant Reformers, this was a sign of God’s grace toward his chosen people and a way that one could show that he was of the Elect and not the Damned. Once this idea took root, money was transformed from the root of all evil to a sign of divine favor. As Weber explains:

Wealth is thus bad ethically only in so far as it is a temptation to idleness and sinful enjoyment of life, and its acquisition is bad only when it is with the purpose of later living merrily and without care. But as a performance of duty in a calling it is not only morally permissible, but actually enjoined. The parable of the servant who was rejected because he did not increase the talent which was entrusted to him seemed to say so directly.

To wish to be poor was, it was often argued, the same as wishing to be unhealthy; it is objectionable as a glorification of works and derogatory to the glory of God. Especially begging, on the part of one able to work, is not only the sin of slothfulness, but a violation of the duty of brotherly love according to the Apostle’s own word.

Weber also quotes a 1736 tract from Benjamin Franklin, the son of a Calvinist, as an example of the Capitalist mindset. While Benjamin Franklin is hardly a sterling example of Calvinism, or of religion in general, Weber also noted that most of the Capitalists of his day had internalized these Protestant ideals toward money and commerce while jettisoning spiritual beliefs.

For six pounds a year you may have the use of one hundred pounds, provided you are a man of known prudence and honesty.

He that spends a groat a day idly, spends idly above six pounds a year, which is the price for the use of one hundred pounds.

He that wastes idly a groat’s worth of his time per day, one day with another, wastes the privilege of using one hundred pounds each day.

He that idly loses five shillings’ worth of time, loses five shillings, and might as prudently throw five shillings into the sea.

He that loses five shillings, not only loses that sum, but all the advantage that might be made by turning it in dealing, which by the time that a young man becomes old, will amount to a considerable sum of money.

With the Reformation’s destruction of monasteries and nunneries, many of Britain’s poor lost their social safety net. The cloister was replaced by the workhouse, where the impoverished and homeless were put to work at menial tasks in an effort to accustom them to manual labor and instill an industrious spirit. When the residents did the bare minimum of unpaid labor, it was taken as evidence that they were worthless idlers. As prosperity was a sign of virtue, poverty was now the fruit of sin.

Out of the Reformation came an Enlightenment that gave birth to two Revolutions. The Industrial Revolution blackened London’s skies and drove peasants who had farmed the land for millennia into filthy slums where they toiled in dangerous factories alongside their children. In France and Russia, its sister slaughtered nobles, clergy, and other undesirables in her dream of destroying both Church and State.

Empires fell and rose. The Spanish, Portuguese, British and French Empires moved toward their steam and gunpowder-powered zeniths. And in 1859 Charles Darwin released The Origin of Species and introduced the world to the Theory of Evolution.

The Calvinists believed the poor were damned. Eugenists believed the poor were genetically inferior. By breeding out the physically and mentally deficient, they hoped to create a smarter, stronger, and happier humanity. The forces of heredity were as inexorable to them as predestination was to their Puritan forebears. Once a duty to God and a sign of His favor, industriousness and profit became the duty of the species and a sign of one’s superior breeding.

American writer Horatio Alger became famous for his stories of industrious Gilded Age urchins who pulled themselves up by their bootstraps. His readers cheered on the plucky heroes and assumed all the other urchins were simply too lazy to put in the work required to rise above their station. His stories helped crystallize an American myth that any talented person would rise to success if only they tried hard enough. There was no lack of opportunity, just a lack of determination and hard work.

After the Great Depression and the war to end all wars, the new American Empire enjoyed a generation of unparalleled prosperity. Factory workers who once lived in slums and company towns now owned suburban houses and vacation homes. Working-class children who once toiled amidst machines now went to college and entered the professional class. They had no reason to doubt that anybody who worked hard in America would prosper.

Any hopes we ever had of a Great Society died in the Reagan Revolution. The next decades saw the gap between the rich and the poor growing ever-larger, and as Christianity declined the Protestant work ethic became decidedly more predatory. We admired the biggest sharks in the tank, the financial overlords who rose to power by eating their competitors. The Gilded Age’s plucky urchins who rose through honest labor grew up to be Gordon Gekko and Patrick Bateman. It was no long enough to be industrious. Those who wanted to get ahead were also encouraged to be ruthless. Those too soft and weak to keep up were soon devoured.

Some have my people have responded to decades of disappointment with prayers to a Prosperity Gospel Christ who wants them to be successful. It is unclear how successful those petitioners have been, but the Prosperity Gospel has certainly made many of its preachers wealthy. Joel Osteen has an estimated net worth of over $100 million, thanks to poor Christians who hoped Jesus would help them get rich.

Flannery O’Connor’s Hazel Motes failed in his efforts to create a Church Without Christ. Those who came after him have been more successful. But the Prosperity Gospel may be the Protestant work ethic’s Ghost Dance. Every day more Americans are turning their back on the dream through “quiet quitting” or simply walking away. And every day more of the people who once would have chastised them for indolence are starting to question why none of their efforts bear fruit.

If you’ve been following my series on the Seven Deadly Sins, you may wonder whether I’m talking about Greed or Sloth. This isn’t entirely surprising, as the Deadly Sins tend to travel in packs. And the Church Fathers would be equally confused by the idea that Christ ordered His followers to go forth and be prosperous. They would also little similarity between what we call idleness and they called Acedia. Which is why, in our next installment, we are going to talk about how our preoccupation with work for work’s sake may in fact be the modern world’s Noonday Demon.

except the ghost dance actually had a purpose rooted in preservation of tradition, religion, culture, and a people. I've always marveled at the appeal of Calvinism, which seems such a bleak and dehumanizing way of looking at the world and salvation.

if you haven't already read it, I highly recommend "The Stripping of the Altars" by Eamon Duffy, also "The Reformation" by Diarmaid McCullough. both point out that once the monasteries and convents had been desecrated and destroyed, the British monarchy found itself with the harsh realization that those places had provided necessary charity to the poor...not something considered in Henry's mad rush to destroy everything Catholic.

An interesting and apt eval., thanks to your invoking Weber and his tremendous insights. Pity that those, though well appreciated by many for a while now, remain unrecognized by so many others at a time of tumult when viable understandings arrived at decades ago have been obscured by politicians and activists who evince little interest in achieving anything on behalf of the rest of us poor slobs other than their own self-agrandizement. So...thanks again!

I am a junior-grade would-be polymath with a decidedly limited skill set. But I did teach world history to inner-city kids at a hard-scrabble high school in south LA - the ‘hood. With no one looking over my shoulder and a crap textbook that no one wanted to read (largely because of underdeveloped reading skills), I wrote-up my own texts for the subject page by page.

In surveying the roots and pathways of modernity it is possible to discern a handfull of crucial revolutions, as you also note. And the painfull transition from the old farm-based subsistence economy is a relevant issue for kids who were born into a remnant of that kind of life, as some of my students from Central American families were. But I missed the connection between the fall of the cloister/nunnery ‘safety net’ and subsequent rise of the workhouse as the ‘protestant work ethic’ morphed into the modern capitalist mindset. Exploring that, especially as an example of the power of ideas, would have been fun and a great exercise for my students. I wish I’d read this 9 years ago when I was deep into my ad hoc process of re-writing the history book!

But allow me to point out a couple things. First of all, my ethnic base is half Dutch, and on behalf of their brief blaze of glory 4 centuries ago, I take a bit of umbrage at your omitting them from the list of Euro-capitalizers/colonizers. Hey, if the Portuguese deserve mention so do the Hollanders! Their extraordinary case also underscores the necessity of a balanced perspective of broad scope when considering that past. They were among the most violent of Reformation iconoclasts, a fact which seems regrettable today. But they also waged an indefatigable fight for independence from Spain and eventually won. And no one today wants to defend the Spanish of the time - particularly the Duke of Alba, right? And they also bequeathed us modern capitalism‘s real roots: ‘high finance.’ Not to mention the fact that they had concurrently developed the purest form of continental Calvinism outside Geneva. So include them in your next update maybe?

Also, to be fair, recall the Calvinist emphasis on literacy and the motive for that. That seems unimpeachable given the circumstances at the time. If greed seems to have prevailed in the end, it clearly must still answer claims laid by those for whom literacy’s revolutionary impact is of undeniable importance. People such as you and me.