[T]he torment of despair is precisely this, not to be able to die. So it has much in common with the situation of the moribund when he lies and struggles with death, and cannot die. So to be sick unto death is, not to be able to die — yet not as though there were hope of life; no, the hopelessness in this case is that even the last hope, death, is not available.

When death is the greatest danger, one hopes for life; but when one becomes acquainted with an even more dreadful danger, one hopes for death. So when the danger is so great that death has become one’s hope, despair is the disconsolateness of not being able to die.

Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death, 25

Pride is at the beginning of every Deadly Sin. Despair is its inevitable end. Sometimes it comes when we face the consequences of our misdeeds. At other times, we realize that our misdeeds are no longer fun. Every thrill becomes commonplace and every vice loses its savor. And sooner or later every self-made individual finds their new identity no longer fits.

When we realize that there is nothing that will satisfy us, our Acedia becomes Despair. If we continue in our vices, it is only because we can think of nothing better. If we give up our old faults, we find no joy in our new ones. We may seek out new virtues and new beliefs, but soon discard them after the excitement wears off. Finally, we lose all hope that joy will ever return.

[S]o much is said about wasted lives — but only that man’s life is wasted who lived on, so deceived by the joys of life or by its sorrows that he never became eternally and decisively conscious of himself as spirit, as self, or (what is the same thing) never became aware and in the deepest sense received an impression of the fact that there is a God, and that he, he himself, his self, exists before this God, this gain of infinity, which is never attained except through despair.

The Sickness Unto Death, 40

For proto-Existentialist Søren Kierkegaard, this constant searching is a sign of deep despair. To be human is to partake both of the temporal and the infinite. But yet, even in nominally Christian 19th Century Denmark, Kierkegaard found that most spend their entire lives thinking themselves mere creatures of time and place. He insisted we could only escape despair and become ourselves by recognizing our place before the Infinite and developing a relationship with the Infinite God.

To be made by God in his image is a fearful thing. To be remade by God is even more terrifying. It is a sculpting that takes place in the deepest parts of our interior lives. In Concluding Unscientific Postscript Kierkegaard talks of the religious man as a “knight of the hidden awareness.” Profoundly changed internally, the religious man is in no ways distinguishable from the temporally focused NPCs around him. He is illuminated by a God he can neither sense nor understand but believes.

As humans, we are also caught between the Possible and the Necessary. Today we prioritize the Possible, and assume anything deemed Necessary must be subjected to criticism and deconstructed. Kierkegaard recommended we focus not on what we can be but on what we must be, lest we fall into the despair of possibility, wherein:

The self becomes an abstract possibility which tires itself out with floundering in the possible, but does not budge from the spot, nor get to any spot, for precisely the necessary is the spot; to become oneself is precisely a movement at the spot. To become is a movement from the spot, but to become oneself is a movement at the spot.

Possibility then appears to the self ever greater and greater, more and more things become possible, because nothing becomes actual. At last it is as if everything were possible — but this is precisely when the abyss has swallowed up the self.

Sickness Unto Death, 54

Kierkegaard also had harsh words for determinists and fatalists who decide there is no possibility, only necessity. Like Sartre a century later, Kierkegaard believed we are condemned to be free. But where Kierkegaard believed that our only hope lies in choosing the possibility of following God and putting ourselves in His service. To be separated from God is to despair. Sartre rejected God, but he was well acquainted with the despair of living in a world where hell is other people.

Today we are encouraged to “find ourselves.” Choosing our gender, finding our fursona, screaming our tribal slogans, promoting our preferred perversions — we have all sorts of identity markers that simultaneously set us apart as individuals and provide us entrance into a chosen community. If we don’t like our new self, we can swap it for another with a new haircut and wardrobe. Never have we had such freedom to create ourselves in our own image. Yet for all that, we appear historically unhappy.

In the Christian West, therapy was largely handled by spiritual leaders. The despairing went to their confessor or spoke with a local holy man. These religious professionals provided lay people advice on how to overcome one’s failings and encouraged them to keep their minds on holy things.

Counselors rely on a variety of therapeutic modalities that help patients see their dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors and find a truce between their warring instincts and inhibitions. Today there are many flavors of psychotherapy, but therapists have largely been deprecated in favor of a pharmacological approach.

Modern-day antidepressants have a much higher therapeutic/lethal index than the original tricyclic antidepressants. If a depressed patient swallows a 30-day dose of Prozac or Zoloft they’ll likely get nothing more than an evening of vomiting, drowsiness, and an elevated pulse rate. A 30-day dose of a tricyclic will almost certainly kill you without immediate medical intervention. And, conveniently, an SSRI prescription costs considerably less than a month of therapy sessions.

As a result, many medicate their Despair with neither priest nor therapist to address its roots. They are now able to tolerate their lives, but they have nobody to offer them advice on how they might improve them. And so they go on leading quiet lives of quiet if somewhat less intense dissatisfaction and disappointment thanks to pills that can give them neither contentment nor release.

Despair, like pain, is a warning system. It can be a spur toward important life changes. Many people have what medieval physicians called a Melancholic temperament. Some are so prone to despair that they need medication to lift themselves out of the endless darkness. Others are dissatisfied because their lives are dissatisfying.

Existential frustration is in itself neither pathological nor pathogenic. A man’s concern, even his despair, over the worthwhileness of life is an existential distress but by no means a mental disease. It may well be that interpreting the first in terms of the latter motivates a doctor to bury his patient’s existential despair under a heap of tranquilizing drugs. It is his task, rather, to pilot the patient through his existential crisis of growth and development.

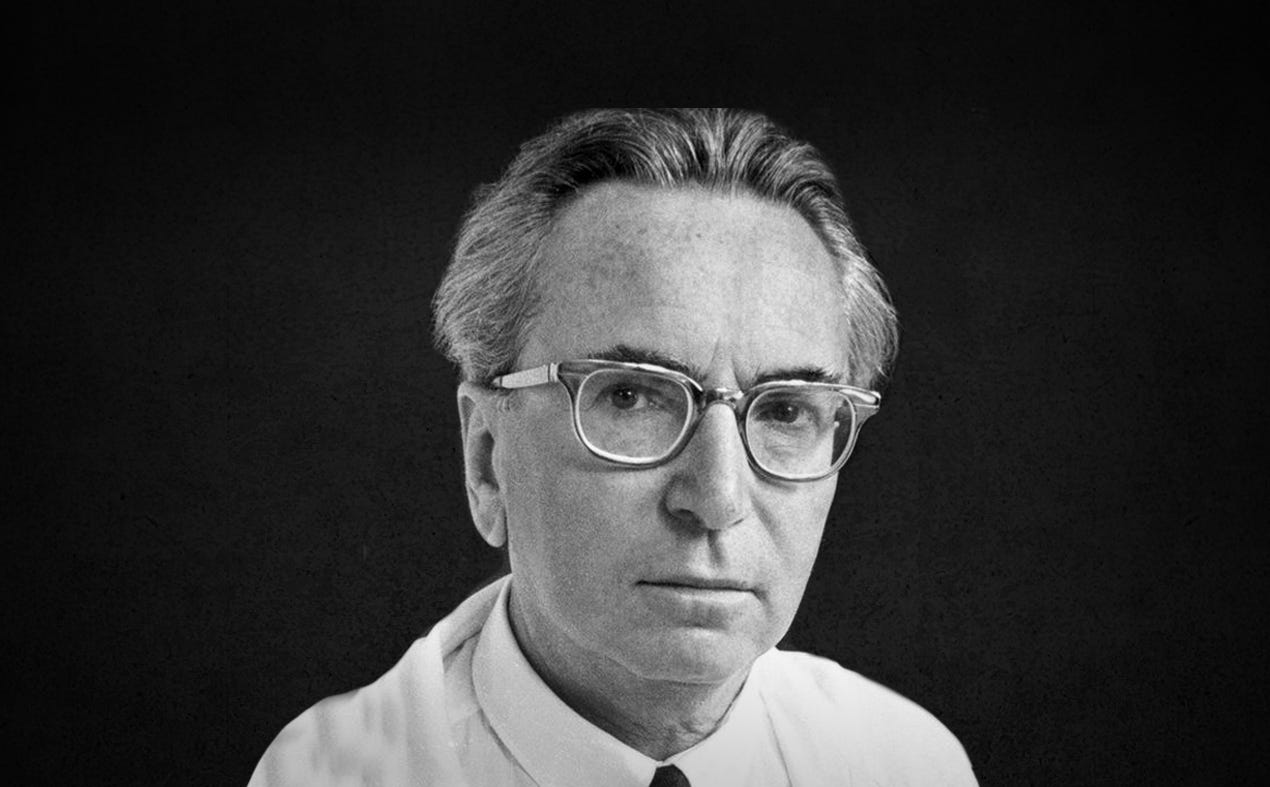

Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, 125

Austrian psychologist Viktor Frankl sketched out his ideas for logotherapy in 1920s Vienna salons. He perfected them in 1942-45 in several different concentration camps. In 1946 he fulfilled the goal that kept him alive through his ordeal, Ein Psychologe erlebt das Konzentrationslager [A Psychologist in the Concentration Camp], later translated into English as Man’s Search for Meaning.

Freudian analysis focuses on the pleasure principle. Adlerian analysis focuses on the will to power. Frankl’s logotherapy focuses instead on our will to meaning. We want both our joy and our suffering to make sense. If we cannot find their meaning, we sink into apathy and despair.

In his 1984 postscript to Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl blamed the drug crisis and other issues on the emptiness and meaninglessness of the Industrial Era’s “existential vacuum.” As we move forward into the post-Industrial Era, that existential vacuum is sucking harder than ever. In that postscript, Frankl also described the three main avenues on which one arrives at meaning in life.

The first is by creating a work or doing a deed.

The second is by experiencing something or encountering someone; in other words, meaning can be found not only in work but also in love…

Most important, however, is the third avenue to meaning in life; even the helpless victim of a hopeless situation, facing a fate he cannot change, may rise above himself, may grow beyond himself, and by so doing change himself. He may turn a personal tragedy into a triumph.

Frankl, 170.

Today we are given lots of choices in our search for meaning, but very little in the way of guidance. And since we are pack primates, we can’t help but search desperately for a leader who will guide and protect us. Industries have grown up around “influencers” telling rapt audiences what to buy, how to dress, and whom to hate.

We complain about “NPCs” and “bots” spouting things with disagree with, but are offended when those brainwashed zombies throw the same accusations at us. We can no longer recognize our fellow humans because we have forgotten what it is to be human. And so we chase after the right wardrobes and the right slogans like baby monkeys clinging to a terrycloth mother in search of comfort.

Kierkegaard found solace in a relationship with God. Frankl found meaning in survival and dignity. The modern world would rather soothe our discontentment with comfort and stimulation. Nihilism and ennui became fashionable. America scorned the lazy sluggard but cheered the Lone Wanderer as he drifted from place to place searching for a peace he would never find. We recognized the Outcast’s acedia as our own, and followed his fruitless path into the desert.

So how do we transform our despair into something meaningful? Tune in for our next episode, and don’t forget to like and subscribe.

I feel as though our respective essays today came at the same idea through two approaches.