“Envy” and “jealousy” are frequently treated as synonyms, but they have distinct meanings. As psychologist Katherine Chan describes it:

Envy involves wanting what someone else has and jealousy involves feeling threatened that someone will take away something you have

In his 1999 book Understanding Domestic Homicide, Neil Websdale found that almost 50% of men who killed their intimate partners were obsessively jealous. For that reason, scientists, counselors, and therapists have paid far more attention to jealousy than envy. Envy typically leads to gossip and backbiting. Jealousy often leads to violence.

To get a better idea of the differences and similarities between envy and jealousy, let’s turn to one of William Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies.

EMILIA

But jealous souls will not be answer'd so;

They are not ever jealous for the cause,

But jealous for they are jealous: 'tis a monster

Begot upon itself, born on itself.

DESDEMONA

Heaven keep that monster from Othello's mind!

EMILIA

Lady, amen.

Othello, Act 3, Scene 4

Iago is simultaneously Shakespeare’s least and most ambiguous villain. He shows no remorse for his various treacheries and misdeeds, but neither does he provide any clear reason for why he despises Othello. Iago is clearly a bad man who does bad things, but we are never told exactly what has led him down his dark and twisted path.

Coleridge referred to the explanations Iago provides in his soliloquies — Othello gave Cassio a promotion he felt was rightly his, Othello and Cassio may have seduced his wife — as “the motive-hunting of motiveless Malignity.” Because motivation plays a key role in modern dramaturgy, we have seen many efforts to figure out what makes Iago tick: psychopathy, sublimated homosexuality, racism, or other neat explanations. Coleridge had a clearer understanding:

Rather seek to learn what his objects in general are! What does he habitually wish? habitually pursue? and thence deduce his impulses, which are commonly the true efficient causes of men's conduct; and without which the motive itself would not have become a motive...

Without the perception of this truth, it is impossible to understand the character of Iago, who is represented as now assigning one, and then another, and again a third, motive for his conduct, all alike the mere fictions of his own restless nature, distempered by a keen sense of his intellectual superiority, and haunted by the love of exerting power, on those especially who are his superiors in practical and moral excellence.

Iago has the ear of powerful men. He is well-respected by his peers and by his superiors. But he cannot swallow his hatred for all who are above him, nor can he explain it even to himself. And so he uses the weapon he knows best — jealousy — to destroy Othello. He wants to believe that Othello and Cassio cuckolded him, because that would justify his hate. Admitting that he envies Othello would mean acknowledging that Othello is his superior.

In his heart Iago knows he has chosen evil over good. His efforts to justify his hate are the last stirrings of what was once his conscience. Like Othello, he lets his passions drive him to inevitable tragedy. But where jealousy drives the Moor to rage, it drives Iago to cold calculation. He knows that in destroying Othello he will destroy himself, but considers it a fair bargain. As he explains in the opening scene:

For when my outward action doth demonstrate

The native act and figure of my heart

In compliment extern, 'tis not long after

But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve

For daws to peck at: I am not what I am.

Iago is but 28 years old when the play begins, and already he has risen to become Othello’s trusted ensign. He will have many chances to rise further, if only he applies his considerable strategic intelligence to productive affairs. But Iago cannot be content with waiting and working honestly. His thwarted ambition for success has been twisted into an appetite for destruction. He is willing to suffer any loss so long as Othello suffers a greater one.

Iago uses his talents to play upon Othello’s insecurities. Othello feels himself dark and uncouth amongst the better-educated, lighter-skinned Venetians. He has trouble believing that a high-born noblewoman like Desdemona could truly love him. Iago feeds those doubts until Othello, consumed by jealousy, slaughters his innocent bride.

Both Othello and Iago are driven by a sense of wounded honor. Othello fears that Desdemona’s infidelity will make him a figure of public scorn. Iago attempts to justify his hatred by imagining the wrongs that Othello and Cassio have done to him. But in Act V.I he lets slip the mask slip when he declares of Cassio:

He hath a daily beauty in his life

That makes me ugly

Othello loves his wife for her beauty and her goodness. Iago hates Othello and Cassio for their nobility of spirit. Othello’s tragic flaw lies in his passions. With Iago, the rot has consumed his soul. Othello destroys goodness that he mistakenly believes to be corrupted: Iago destroys goodness because it reminds him of his corruption.

French polymath René Girard is most remembered today for his mimetic theory. We have long known that humans learn through imitation. Girard was the first to note that we also learn desire through imitation.

We want things because others want them. Advertisers use celebrity endorsements and “influencers” to convince prospective buyers that their wares are desirable. We trust the slogans we repeat because our peer group has declared them correct and accurate. And we choose our romantic partners because we think others will also find them attractive. As Girard puts it in his 1991 Shakespeare study A Theatre of Envy:

Our desires are not really convincing until they are mirrored by the desires of others. Just below our fully explicit consciousness, we anticipate the reactions of our friends and try to channel them in the direction of our own uncertain choosing, the direction that our desire should steadfastly maintain in order not to seem mimetic at all.

But in learning desire through mimesis, we set ourselves up for interpersonal conflicts. Girard points out that much of the dramatic tension in Shakespeare’s works comes from mimetic misunderstanding. Before Othello meets Desdemona, he is befriended by her father, a wealthy nobleman who loves listening to the Moor’s wartime stories. Soon father and daughter are both enchanted by Othello’s tales. But their shared mimetic joy is soured when Desdemona elopes with the storyteller.

For Othello, Desdemona represents acceptance into Venetian society. But with mimesis comes insecurity. Othello has won the love of a beautiful noblewoman, but fears he is unworthy of her and that others who recognize her beauty will win her heart. These fears become an obsessive jealousy which ultimately destroys both the lover and the beloved.

Iago saw himself as a close confidant to a man he admired. He built his identity around his relationship to Othello, much as many today build their persona around their job or their friends. When Othello disappointed him, Iago’s identity was shattered. In his efforts to rebuild his identity, Iago found himself both feeding his hatred and resisting his remaining affection for the Moor.

At the end of Act 2 Scene 1, Iago proclaims:

The Moor, howbeit that I endure him not

Is of a constant, loving, noble nature,

And I dare think he’ll prove to Desdemona

A most dear husband. Now, I do love her too,

Not out of absolute lust (though peradventure

I stand accountant for as great a sin)

But partly led to diet my revenge

For that I do suspect the lusty Moor

Hath leaped into my seat—the thought whereof

Doth, like a poisonous mineral, gnaw my inwards,

And nothing can or shall content my soul

Till I am evened with him, wife for wife,

Or, failing so, yet that I put the Moor

At least into a jealousy so strong

That judgment cannot cure…

I’ll have our Michael Cassio on the hip,

Abuse him to the Moor in the rank garb

(For I fear Cassio with my nightcap too),

Make the Moor thank me, love me, and reward me

For making him egregiously an ass

And practicing upon his peace and quiet

Even to madness.

By his own telling, Iago’s hatred of Iago begins when he is passed over for a position as Othello’s second-in-command. But Othello by all appearances still holds Iago in high regard despite appointing Cassio lieutenant. It is not hard to envision Iago as a hero-worshipper idolizing his charming, brilliant commander. Nor to imagine his adulation turning to hatred as he discovered that Othello did not place him on an equally high pedestal.

Other ills have their limit; and whatever wrong is done, is bounded by the completion of the crime. In the adulterer the offense ceases when the violation is perpetrated; in the case of the robber, the crime is at rest when the homicide is committed; and the possession of the booty puts an end to the rapacity of the thief; and the completed deception places a limit to the wrong of the cheat.

Jealousy has no limit; it is an evil continually enduring, and a sin without end. In proportion as he who is envied has the advantage of a greater success, in that proportion the envious man burns with the fires of jealousy to an increased heat.

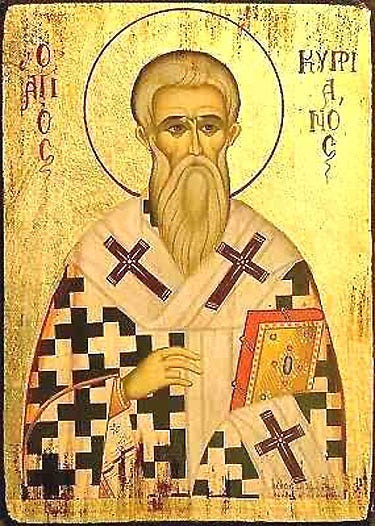

St. Cyprian of Carthage, Treatise 10 “On Envy and Jealousy”

In 3rd Century Carthage, as in the modern world, many considered envy to be a venial sin. St. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage, worked very hard to convince them otherwise in his treatise “On Envy and Jealousy.” Cyprian pointed out that all Satan’s works are done out of jealousy and envy: after losing his own salvation, Old Splitfoot has worked ceaselessly to ensure on one else finds their way to heaven.

During the time he was writing this treatise, Cyprian faced resistance from clerical factions and an antipope who had set himself up in place of the lawfully elected St. Cornelius. He saw these internecine squabbles as rooted in envy and hoped to discourage further discord amongst the faithful.

Like other writers of his time, Cyprian uses the Latin invidia (envy) to describe both envy and jealousy. The division between the two concepts comes only in the late Medieval era, when the French began using the word gelos, from the Latin zelos (zealous) to describe a spurned lover’s unseemly passion. While this may cause momentary confusion among modern readers, it also helps us see the places where envy and jealousy converge.

St. Cyprian notes several Old Testament examples of jealousy. After God favors Abel’s sacrifice, Cain commits the first fratricide and then seeks to cover up his crime. After Jacob receives his father’s blessing, his brother Esau declares war on him. Joseph’s coat of many colors drives his jealous brethren to sell him into slavery. And David’s victory over Goliath drives King Saul to murderous rage.

St. Cyprian, like Shakespeare and Bertrand Russell, recognized the way envy and jealousy eats us from the inside. All our joys become tainted by our fear that someone else is having more fun than we are. The target of our envy looms eternally before our eyes. As Cyprian tells us:

Whoever he is whom you persecute with jealousy, can evade and escape you. You cannot escape yourself. Wherever you may be, your adversary is with you; your enemy is always in your own breast; your mischief is shut up within; you are tied and bound with the links of chains from which you cannot extricate yourself; you are captive under the tyranny of jealousy; nor will any consolations help you.

I really like how you brought science, history and literature together to support your main point.