6th Century Byzantium had rioting Greens and Blues. 12th and 13th Century Italy saw conflict between Guelphs and Ghibellines. 19th Century America had a disagreement amongst Yankees and the Rebels. 20th Century America saw the Hippies square off against the Establishment. Every generation has its Manichaean struggle between Good (us) and Evil (them).

Today our battle plays out between the Left and the Right. Folks on the Right call Lefties Demonrats, Communists, Shitlibs, Snowflakes, etc. Folks on the Left call Right-leaning types Christofascists, Trumptards, MAGAts, Nazis, etc. Each side sees the other not as misguided but as demonic.

Manichaean conflicts can spark bloody brother wars. But they can also be used to divide an angry populace and keep the plebes distracted from their real oppressors. To understand our current Great Divide, let’s take a look at where this split began.

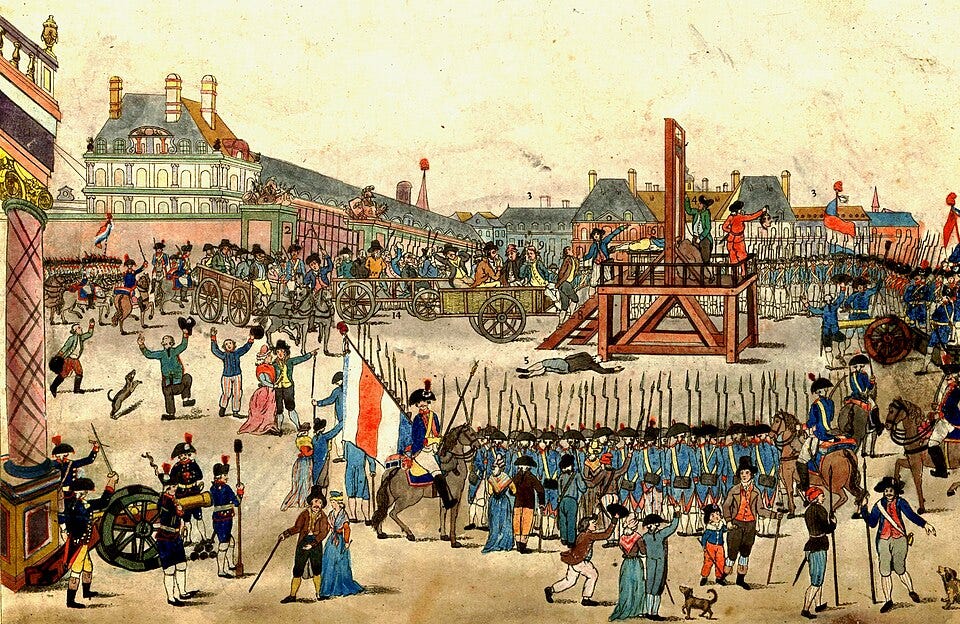

By 1789, Louis XVI was facing opposition from all of France’s Estates. The country teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. But the First and Second Estates (clergy and nobility, respectively) were dead set against any financial reforms that might affect their wealth. After two years of bad harvests, the country’s poor were famished and the Third Estate’s bourgeois commoners were throwing around words like liberty, freedom, and equality.

In a last desperate attempt to salvage his crumbling kingdom, Louis called a meeting of Les États généraux (the Estates General). Not since 1614 had the Estates General been called together. By bringing together these representatives, King Louis hoped the squabbling estates could hammer out some kind of a compromise.

Unfortunately, the three Estates wound up deadlocked on the first question: how much power should the King have to veto decisions agreed upon by the Estates? The squabbling parties organized themselves by their position by their chosen seats. Those who favored a strong monarchy sat on the right-hand side of the dais. Those who wanted more power for the Estates sat on the left.

As you may have guessed, the left won that conflict. When Louis tried vetoing orders, the Third Estate declared itself the National Assembly and refused to listen to the other two Estates. Before long the Bastille was stormed and the government overthrown. King Louis XVI was demoted to Citoyen Louis Capet and later executed.

America has neither a king nor an aristocracy. Most of our self-described Right-wingers would have been firmly on the side of the Left in the 1789 Parliament. (To be fair, they would have wound up meeting Mme. Guillotine when their fellow Leftists decided they were Jacobins in Name Only.) We’re great-great-grandchildren of the Enlightenment. Ideas that shocked the 18th Century are taken for granted in the 21st.

While America has always been more fervently religious than post-Enlightenment Europe, we have never had an official state religion. Many Left-identified people believe that the Right is full of Fundamentalists who want to blow up abortion clinics and force all women back into the kitchen. While a talented preacher can gain a great deal of political power, there is no American First Estate.

America’s Left has mimicked the National Assembly’s purported concern for the people. But that concern has largely been focused on “oppressed groups” while the majority of working and non-working poor are treated with a contempt that would raise eyebrows amongst the snobbiest Second Estater. And while the Right in 1789 France pushed for greater royal power, today’s Right has a decidedly Libertarian bent.

The “Left/Right” split has not only deviated from its original meaning, it’s become almost meaningless. For example, there is far less political difference between Obama and George W. Bush than there was between Stalin and Trotsky. And yet most could say that Barack is Left and Dubya is Right, while both Stalin and Trotsky would be labeled Leftists. We scream obscenities across an aisle that no longer exists.

Let’s take a look at some of our other dividing lines.

One of the expedients of party to acquire influence within particular districts is to misrepresent the opinions and aims of other districts. You can not shield yourselves too much against the jealousies and heartburnings which spring from these misrepresentations; they tend to render alien to each other those who ought to be bound together by fraternal affection.

George Washington’s Farewell Address, September 17, 1796

George Washington, and most of the other Founding Fathers, considered political parties detrimental to the functioning of a healthy republic. They feared partisanship would lead to strife and dissension within their nascent Republic, and that parties would prioritize their own concerns over those of the people. They even warned that parties could become corrupted by donations from foreign governments or wealthy benefactors.

But almost immediately after Washington’s retirement to Mount Vernon, legislators split into Federalist and anti-Federalist camps. The Federalists (led by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams) favored a strong central government and closer ties with Great Britain. The anti-Federalists (led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison) advocated for states’ rights and closer ties with revolutionary France.

But while the Federalists were popular with the wealthy and educated, the people were much more aligned to anti-Federalist causes. They saw the Federalists as arrogant, out-of-touch aristocrats who prioritized the rights of bankers and speculators over working folk. By 1824 all four Presidential Candidates were members of the anti-Federalist party, which now called itself the Democratic-Republicans.

Alas, the 1824 election was hotly contested and left lots of bad blood in its wake. Andrew Jackson won a plurality of votes, but John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay made an agreement that put Adams in the White House. Their supporters came to be known as National Republicans and later as Whigs. Meanwhile, Jackson defeated Adams in the 1828 election with the help of his Democratic Party.

In 1840 Whig candidate William Henry Harrison won the Presidency. But after serving only a month in office, Harrison died of enteric fever. His vice-president, John Tyler, was soon drummed out of the Whigs for his support of the national bank and his distaste for tariffs. Not until 1848 would the Whigs win back the Presidency under Zachary Taylor.

But within a year Taylor was dead. His successor, Millard Fillmore, was unable to manage the tensions between the northern and southern Whigs over the slavery issue. In 1852 Democrat Franklin Pierce came to office, and after him James Buchanan, another pro-slavery Democrat. By that time the pro-slavery Whigs had largely joined the Democrats while anti-slavery Whigs had rebranded themselves as Republicans. In 1860 we saw our first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln.

Republican stalwarts never tired of commenting that Lincoln ended slavery while Democrats sought to preserve it, and that Dems later fought hard for segregation. They’re less likely to note that Donald Trump’s politics are closer to Andrew Jackson than to John Quincy Adams. And partisans fall silent when you note that politicians on all sides, as per George Washington’s prediction, are more interested in their place at the money trough than the well-being of their voters.

After the Red Scare, Commie-baiting became decidedly unfashionable amongst educated Americans. When the Soviet Union fell, it seemed we had won for good. Reds were no more a threat to the American way of life than Redcoats. Lawsuits and arrests had broken the Klan, the Aryan Nations, the American Nazi Party, and most White Supremacist organizations. We might have expected both groups would have faded into memory. As you may have noticed, that didn’t happen.

The medieval world had Judas Iscariot; the 21st Century has Adolf Hitler. Who would have thought that a failed Austrian painter could rise to such heights, then fall to such infamy? His name has become a synonym for Caucasian Perfidy and Genocidal Tyranny. And the party he led remains a shadowy terror ready to goose-step their way back to power at any moment.

For those who hate Communism and love Democracy, Josef Stalin remains the preferred cliche. They correctly point out that Stalin killed more people than Hitler. Some will even mention Zedong Mao, though neither Uncle Joe or Chairman Mao reached the per capita death tolls achieved by Pol Pot. But while even most self-identified Right-wingers will denounce Hitler and declare Librulz R the Real Nazis, Communist dictators don’t get nearly so much hate as Uncle Adolf.

That being said, “Communist” has become as nebulous as “Nazi.” Just as there are those who believe every Republican is a National Socialist, there are some who believe every Democrat is a card-carrying Communist — as were the National Socialists. (“It’s in their name, duh!”) At this point insulting someone as a Nazi or a Communist says more about your politics than theirs.

A few earnest folks still tweak the Conservatives with Karl Marx and Che Guevara T-shirts. Others seek attention by posting pictures of concentration camps or goose-stepping Gestapo. But this is largely a case of style over substance. They may talk about overthrowing the system or sending Shlomo to the showers. But they have neither the guns, the gas, nor the will to implement a revolution or a putsch.

When Napoleon was finally exiled to St. Helena, he was reviled as a bloody tyrant. By the mid-20th century, comedians regularly impersonated madmen who thought they were Napoleon. Things move faster today. 75 years after World War II, there’s a whole generation that knows Adolf Hitler best by way of “oven memes.”

Overheated accusations against NAZIS!!! and COMMIES!!! have taken the sting out of the accusation. When everybody is a genocidal dictator, then nobody is a genocidal dictator. Ultimately this dividing line, like the others, gets increasingly fuzzy the more you focus on it.

After two world wars, midcentury America was sick of conflict and bloodshed. Americans wanted Peace. They wanted Freedom. They wanted Democracy. But then, as now, they found themselves asking what those words mean. In 1949 semanticist Samuel Inouye (S.I.) Hayakawa addressed the issues of what words mean -- and what they can do -- in Language in Thought and Action.

Semantics explores how the auditory and verbal cues we produce (what those not in academia call "oral and written language") shape our identity and society. Words are the map by which we understand our world. But those words can convey falsehood as well as truth, and error as well as fact. And, as Hayakawa noted, many words say only "I have strong feelings."

We are a little too dignified, perhaps, to growl like dogs, but we do the next best thing and substitute series of words such as "You dirty sneak!" "The filthy scum!" Similarly, if we are pleasurably agitated, we may, instead of purring or wagging the tail, say things like "She's the sweetest little girl in all the world!"

Hayakawa called these utterances snarl-words and purr-words. He also noted that much political discourse consisted largely of these raw spillages of emotion. All the divisions above are, in the end, snarl words. They express emotions, not facts. Those who use them are making shows of dominance and establishing themselves as pack members. Arguing with them is like trying to reason with a growling dog.

Because we’re pack primates, snarl words can be very effective tools of control. Nothing brings us together like a common enemy. And if you organize different packs around a whole bunch of different common enemies, you can ensure that no single pack ever gets big enough to take yours down.

Many who lack power in their personal lives have found its semblance online. By declaiming their hate for the proper targets, they imagine they are making a difference. Give a Chihuahua a toy to chew on and it will happily pretend it’s a Doberman. And because that Chihuahua is incapable of doing serious harm, its owners can tolerate or even have a laugh at its yapping.

If you want to make a difference, you must rise above these false dichotomies. People who say mean things can be safely ignored. You need to focus on the people who can hurt you. In a war your enemy will make himself known soon enough. And the only divide that will matter is the one between those who will fight and those who won’t.

Excellent work.

The boo-hurrah school tend to go a bit further than the coding of Bentham and say there’s nothing more to morality than this sort of emotional noise. Of course there is - and knowing (and telling) the difference between mere noise and signal is another means of distinguishing friend from enemy.

You are an interesting fellow Kenaz, and this is a piece worth anyone’s time. Well said.